- Home

- David Bradford

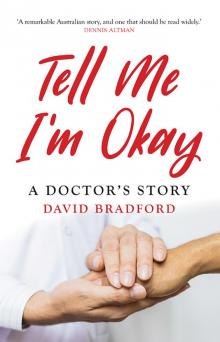

Tell Me I'm Okay Page 5

Tell Me I'm Okay Read online

Page 5

When I first arrived in Vietnam, the regiment was under the command of the second-in-command (the 2IC).9 Our own CO and the last contingent of gunners arrived a couple of weeks after I did. He soon called me in for a briefing.

‘David,’ he said, ‘well done! Since I’ve arrived, I’ve been around the regiment talking to the men. It seems that everyone knows you already, which means you’re doing your job. Keep it up!’

A gay man once asked me what life was ‘really like’, at Nui Dat. Jokingly, but none the less truthfully, I told him that, visually, Nui Dat was paradise for a gay man. Good-looking, well-built young men were everywhere, mostly wearing very little during day-light hours – just shapeless Army shorts, socks, and boots. There were no women, and it was always hot and airless under the rubber trees. During the day, few soldiers or junior officers ever wore shirts.

Out on operation, at FSBs in the bush, when not firing the guns, time hung heavy on the men’s hands. Some gunners vied with each other to develop the best ‘all-over’ sun tan. On a visit, I might arrive at a gun site to find gunners lying totally naked in the sunshine. It was distracting, but I couldn’t help being inwardly delighted.

Sex, Soldiers and VD

In Vietnam, VD was a headache for senior officers of both the American and the Australian Army Medical Corps.10 But, VD was not a significant medical problem, as it had been in the pre-antibiotic days of World War I and the early years of World War II. By 1967, the common venereal diseases, gonorrhoea and syphilis, were easily and quickly treated with appropriate antibiotics. Even the tiresome condition, non-specific urethritis (NSU), which we now know is due to chlamydia, responded to treatment, albeit more slowly. Only rarely was hospital referral required. Soldiers did not have to be removed from the war zone, nor put on light duties.

While the medical aspects of having VD were easily resolved, the frequency of VD in Australian and American soldiers in Vietnam, and the accompanying moral issues were the real cause for concern for Army authorities. They were worried about the likely political fallout if the high rates of VD became widely known back home. The topic was the subject of endless discussion in officers’ messes, sergeants’ messes, and the more humble messes of the other ranks (ORs).11

The first night I arrived in Vietnam, an unlikely suspect, one of the chaplains, raised the subject with me in the officers’ mess of 4th Field Regiment. He said lugubriously, ‘Doctor, I hope you know a good deal about VD, because you will need to!’

Our CO, Reg Gardner, was a fine man and I warmed to him more and more as the year wore on. He’d been born in England and was an old-school, gentlemanly, Army officer. He had a tendency to testinesswhich would flare suddenly if something provoked him. His already rather rosy face would flush bright crimson and he would explode with some colourful language. However he was a highly competent gunnery officer with a very kind heart and he cared greatly for all the men under his command. He soon summoned me for a VD discussion. ‘David, I see from your monthly report for May that VD rates are high in all the Batteries.’

‘Yes, Sir. Some gunners had a stopover in Manila for a night on the way here. And there’s always R&R and R&C.’12

‘It’s unfortunate. The Brigadier is concerned about VD rates throughout the Task Force. Apparently, we are not alone. All the Units report the same problem.’

‘Yes, Sir. I understand it’s even worse in the units stationed in Vung Tau.’

‘We need to do something. You had better organise lectures on VD prevention for all the Batteries, including those Kiwis.’

‘Bob Allen and I already have that in hand, Sir.’

‘Good. I hope my officers are supportive and setting a good example?’

‘As far as I’m aware, Sir.’

‘You would let me know the names of any officers not setting a good example, I trust, David.’

‘In what respect, Sir?’

‘Well, were there any officers from this regiment who acquired VD in Manila?’

‘I’m afraid I can’t answer that question, Sir.’

The Colonel’s ruddy cheeks took on a deeper hue. He was becoming testy.

‘Can’t or won’t, Captain Bradford? This is first and foremost a matter of military discipline.’

‘I’m inexperienced in Army ways, Sir. But I know the importance of maintaining medical confidentiality.’

‘Oh, bugger medical confidentiality, Doctor! You have a duty to support me in maintaining good military discipline throughout this regiment. I don’t want the Brigadier thinking we Gunners are no better than the Infantry.’

‘No, Sir. But, what officer is going to feel confident coming to see me if there’s any suspicion I might discuss his case with you, or the 2IC?’

‘I don’t want to know about their bloody blood pressure or what not, but I do want to know if any of my officers have so far forgotten themselves as to run the risk of VD!’

‘With respect, Sir, some of your officers are mere boys. They’re younger than I am.’

‘However young they are, they are officers in the Royal Australian Artillery and will behave as such.’

‘Of course, Sir. But I think that the DGMS, who is visiting the Task Force from Melbourne next week, will support my view.’

‘Well, I hope so, Captain Bradford. I’ll definitely raise the matter when I see him.’

I was shaking as I left him, because I was on shaky ground. I really didn’t know whether Brigadier Gurner would support me. As threatened, the CO raised the matter with him. I was very relieved when the head of the Medical Corps said he shared my view on maintaining medical confidentiality. My CO had the grace to accept his ruling, but other commanding officers were more reluctant. Some months later, a new Major commanding the Cavalry Regiment Squadron, for whom I also provided medical care, tried to pull rank on me. He subjected me to a tirade of colourful language for refusing to disclose whether any of his officers had consulted me about VD.I held my ground and didn’t enlighten him that he had good cause for concern. The ‘tankies’, as members of the Cavalry Regiment were known, were a randy bunch and their junior officers set the standard.

This put me in a strange situation. Whenever possible, I went to the Task Force Chapel on Sunday and I played the harmonium for the Protestant service. I continued to adhere to the Christian principles by which I’d been brought up. I didn’t drink alcohol, didn’t smoke, didn’t swear, and didn’t take part in dirty story telling. I tried to keep my thoughts ‘clean’ – with singular lack of success, I must admit. I had never heard of VD before the final years of medical school, although I later realised it had been hinted at in The Doctor Says, my mother’s sex education handbook. I worried that if anyone should condemn VD sufferers it should be me. I was known as a Christian, yet here I was virtually upholding the right of young officers to behave immorally when off-duty, without any fear of their being dobbed-in to the commanding officer. The truth was that despite my inherited Christian principles, VD was beginning to fascinate me.

A colourful character – Lt-Colonel John Dunn – who, by the time I arrived in Vietnam, was Deputy Director of Army Medical Services (DDMS) in Saigon, had given a couple of very amusing and memorable VD lectures at the Healesville course. He had been an Ear, Nose and Throat Surgeon in civilian life, but had somehow become the Australian Army’s expert on VD. He covered diagnosis and treatment, but concentrated more on simple, realistic hints on VD prevention in the military. He had been very strong on maintaining medical confidentiality. I think his lectures first aroused my interest.

On the practical side, I had gained no experience in managing VD at my teaching hospital so I felt very inadequate at first. But, Bob Allen, my sergeant, was an old hand. He soon brought me up to speed. In the RAP, there was a microscope, microscope slides, and appropriate stains. I was soon an expert at swabbing urethras, making slides, staining and reading them under the microscope. As time passed, I felt more and more empathy with my hapless VD patients and I quickly lost any em

barrassment dealing with the issue.

There were very good reasons for the high rates of VD in the regiment. The gunners were young and fit, most between nineteen and twenty-two years of age. They were in Vietnam for twelve months, cooped up in an all-male camp. Life at Nui Dat, and even on operation at Fire Support Bases outside the Task Force, was tedious. Despite the monotony, there was a background climate of quiet menace throughout the country. No-one knew if, or when, we might be subject to sudden attack. Although statistically speaking, there was only a small chance of a gunner losing his life in Vietnam, the possibility could not be ignored and was never forgotten by any of us.

It was R&R and R&C that produced most cases of VD. On leave for five days, soldiers were left to their own devices – it was difficult for some to adjust to freedom after months of army regimentation. There were ample opportunities for casual sex in all the R&R approved cities (Bangkok, Singapore, Taipei, Manila, Hong Kong and later, Sydney). In their quest for the military dollar, hotel proprietors and tour operators set out to meet the sexual needs of soldiers on R&R. Consideration of moral questions didn’t figure prominently in their decision making. The situation was the same, if not worse, in the coastal ‘resort’ of Vung Tau, where men had their R&C leave. At any one time, there were American, Australian, New Zealand, South Korean, and South Vietnamese soldiers taking leave there and, almost certainly Vietcong and North Vietnamese soldiers as well. I often liked to idly speculate that the gonorrhoea I diagnosed in one of the gunners might well have been brought down the Ho Chi Minh trail from Hanoi by one of Uncle Ho’s men and passed on to my patient via a bar girl in Vung Tau!

Wherever there were soldiers with money but limited time on their hands, there were girls eager to help them spend both. Doctors at the Australian Hospital (8 Field Ambulance) in Vung Tau did their best to test and treat bar girls for VD at weekly clinics in the city, and the Military Police (MPs) provided soldiers on leave with lists of approved bars that sent their girls for regular testing. But it was a preventative drop in the ocean: girls moved freely from one bar to another, soldiers took little notice of the approved lists, there were insufficient MPs to police the bars, and girls treated one day would be reinfected the next. VD rates were unaffected.

R&C leave wasn’t always a happy time for my gunners. Gunner Hyde, one of the barmen in the 4 Field Regiment officers’ mess, was a surly, taciturn man who showed little enthusiasm for waiting on officers at mealtimes in the mess tent, or serving us drinks at the bar. Whatever his future held, one could only hope it was not going to be in the hospitality industry. But, he was good-looking, tall, well-muscled, with full, shapely lips and a hint of underlying sensuality. I suspected he might get into trouble when he went to Vung Tau. Sure enough, two days after he returned to duty, he looked unusually worried and seemed to be paying me more attention than usual as he took our breakfast orders. Had he taken a hospitality course in his five days of leave? I seriously doubted it. Later, I wasn’t surprised to see that he was part of the morning’s Sick Parade at the RAP. When his turn came and he was sitting in front of me in my office, I said:

‘Well, what’s up, Gunner Hyde?’

He sighed heavily:

‘Drippy dick, Doc; but it’s bad – lots of swelling – and it’s fucking hard to piss.’

‘What? Painful to piss?’

‘Bloody oath!’

‘So, you had sex in Vungers?’

‘Coupla’ sheilas.’

‘Bar girls?’

‘Yep.’

‘Which bar, do you know?’

‘No fucking idea, Doc.’

‘You didn’t use condoms?’

‘Too pissed.’

‘Well, you’d better let me look.’

He stood and dropped his shorts. Gunner Hyde had been blessed with an impressively large penis – I had suspected as much, having become well acquainted with the bulge in his pants as he carried out his mess duties. But this morning, it was a sorry sight – the head of his penis was an angry red, swollen to three times its normal size. Copious yellow pus oozed from the urinary opening with several thick drops falling onto the concrete floor as I examined him. An uncomfortable, but irrational, thought flashed through my mind. Less than an hour ago this man had served my breakfast. Fortunately, I knew you couldn’t catch gonorrhoea from food contamination.

I took a blood test for syphilis and, given the state of his penis, I took the necessary swabs as gently as possible. I made a slide and checked it under the microscope.

‘You’ve got the clap, Gunner Hyde.’

‘Thought so, Doc.’

‘It’s definitely gonorrhoea, but you’ve got a nasty complication. All that redness and swelling is due to a condition we call cellulitis.’

‘Can you fix it?’

‘Yes, a shot of Procaine Penicillin today, and one every day for the next three days should do the trick. I’m afraid you’ll have a sore bum for a week or so.’

‘Those fucking, dirty, noggy sheilas down in Vungers!’

‘Takes two to tango, Gunner.’

I hadn’t expected Gunner Hyde to explode. His face quickly flushed with anger and he delivered a tirade:

‘Listen Doc, would you believe that I fucking hate this whole bloody set up, the fucking country, the fucking ‘slopes’,13 the fucking Army, the fucking War? And as for that arrogant little dickhead, the 2IC, bossing me around day after day, I could fucking kill the cunt – in fact, he’s lucky I haven’t. Why couldn’t they have left me alone? I was happy minding my own fucking business in Gympie, doing my job, looking after my girl … and now this fucking SHIT!’

He kicked the wall hard; there were tears of frustration in his eyes.

‘Take it easy John,’ I said gently. ‘We’re all in this shit together. I’ll tell you what I’m going to do. I’ll give you a chit for the 2IC, saying you’ve got bad cellulitis – he doesn’t need to know where – and that you’re going to hospital for three days. Then I’ll ring the Doc at 8 Field Ambulance14 and tell him to expect you. All you need do is collect your toothbrush or whatever, and head up there.’

‘You sure, Doc?’

‘I’m sure. The medics up there are good blokes. Once they see that dick of yours, they’ll give you a bit of a hard time for the fun of it, but they’ll make sure you get the right treatment. I think you could do with a rest from the Officer’s Mess and the 2IC.’

After his injection, Gunner Hyde loped off, looking a little happier. When I made the snap decision to send him to the Field Ambulance, it was the gunner’s mental health I was concerned about, rather than his sexual health. I happened to share his feelings about the 2IC, but didn’t think the cocky little Major deserved to be murdered by an angry barman. I rang my colleague at the Field Ambulance and suggested he sedate Gunner Hyde heavily for the next three days while he completed his penicillin treatment.

There were opportunities for sex even when not on leave. Gunners would seize any chance of a ‘quickie’: on a daily laundry run intoBaria (the provincial centre), driving an officer on Army business to Vung Tau, or coming with my team on a Medcap visit to a local village.15 A couple of gunners even managed to contract VD during a ten minute stopover on a long road convoy. They happened to be travelling in a Land Rover near the head of the convoy. At the stopover, they made their assignation and disappeared into a nearby hut with their chosen ladies. The convoy moved off, but so slow was its progress, the smirking gunners were able to rejoin their fellows in another Land Rover near the convoy’s tail. Temptations were great. In any village, as soon as soldiers appeared, girls were quickly on offer; street urchins ran alongside army vehicles asking for cigarettes, and yelling:

‘Uc-Da-Loi, you want girl? My sister, she number one boom- boom.’16

It was David Garrick, that great eighteenth-century actor, who once said ‘A fellow feeling makes us wondrous kind’, and so I was tolerant with my wayward gunners. I knew how sexually frustrated they were because I felt the same. The

re’s something about being on active service in a war zone that heightens sexual desire. Vietnam wasn’t unique; it’s been documented in every war of the twentieth century and probably occurred in wars even before then. VD was an inevitable consequence.

The more junior officers often gave me a hard time. Bob Birse swore he was going to put an end to my teetotalling days, by force if necessary, and see me drunk before the end of the tour. Sadly, he didn’t live long enough to carry out his threat. The talk in the officers’ mess, after the more senior officers had retired for the night, often turned to sex. One night, the conversation became more than usually raunchy and explicit, no doubt lubricated by the alcoholconsumed. I felt uncomfortable and began blushing. I was about to excuse myself, when Paul Jones, the Battery Captain of Headquarter Battery, turned to me:

‘Now Doc, tell us. What does the medical profession think about cunnilingus?’

I dimly knew what cunnilingus was, but otherwise I hadn’t the slightest idea. I searched my mind for an ‘official’ view. I stammered a little:

‘Well, er, you know. Psychiatrists and most doctors think it’s a form of perversion.’

There was a stunned silence.

‘A perversion, Doc?’

‘Well, yes, I think so.’

There were hoots of derision and much ribald laughter. Even Gunner Hyde, on bar duty that night, smirked.

Fortunately, Paul had a kind heart under his tough exterior. He came to my aid:

‘Sorry, Doc. I was teasing you. We knew you wouldn’t have the faintest idea. Everyone knows your next fuck will be your first.’

In May 1968, my twelve months’ tour of duty in Vietnam ended and I returned to Australia with a plane load of gunners. Although I wasn’t sorry to leave the privations of Nui Dat, during the five weeks on leave that followed I felt sorely bereft. It was as if I had lost something precious and vital to my well-being, like an arm or a leg. I missed the gunners and I missed being the gunners’ doctor. It’s of course not an uncommon feeling. Some wanted to put as much distance between themselves and the Army as possible. Others, however, missed the discipline and pleasures of military life.

Tell Me I'm Okay

Tell Me I'm Okay